On a crisp November evening, a modest home in South Jersey became, for a few luminous hours, the kind of place where Lagos and London quietly collided.

Awwal Adegoke Ayinde, the Nigerian Football Federation scout and seasoned youth coach, marked his 37th birthday not with a gala at a city hotel but with an old-fashioned house party that read like a masterclass in diaspora community life: generous, noisy, ritualistic, and full of meaning.

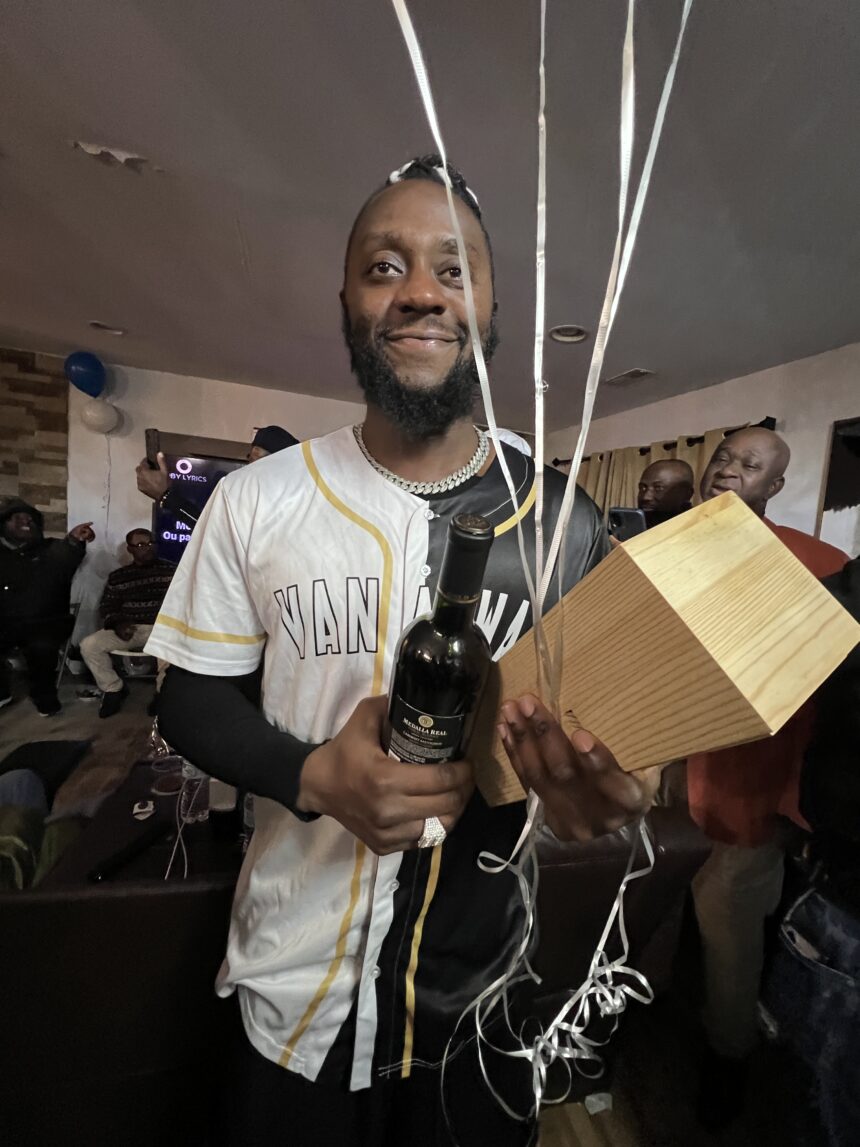

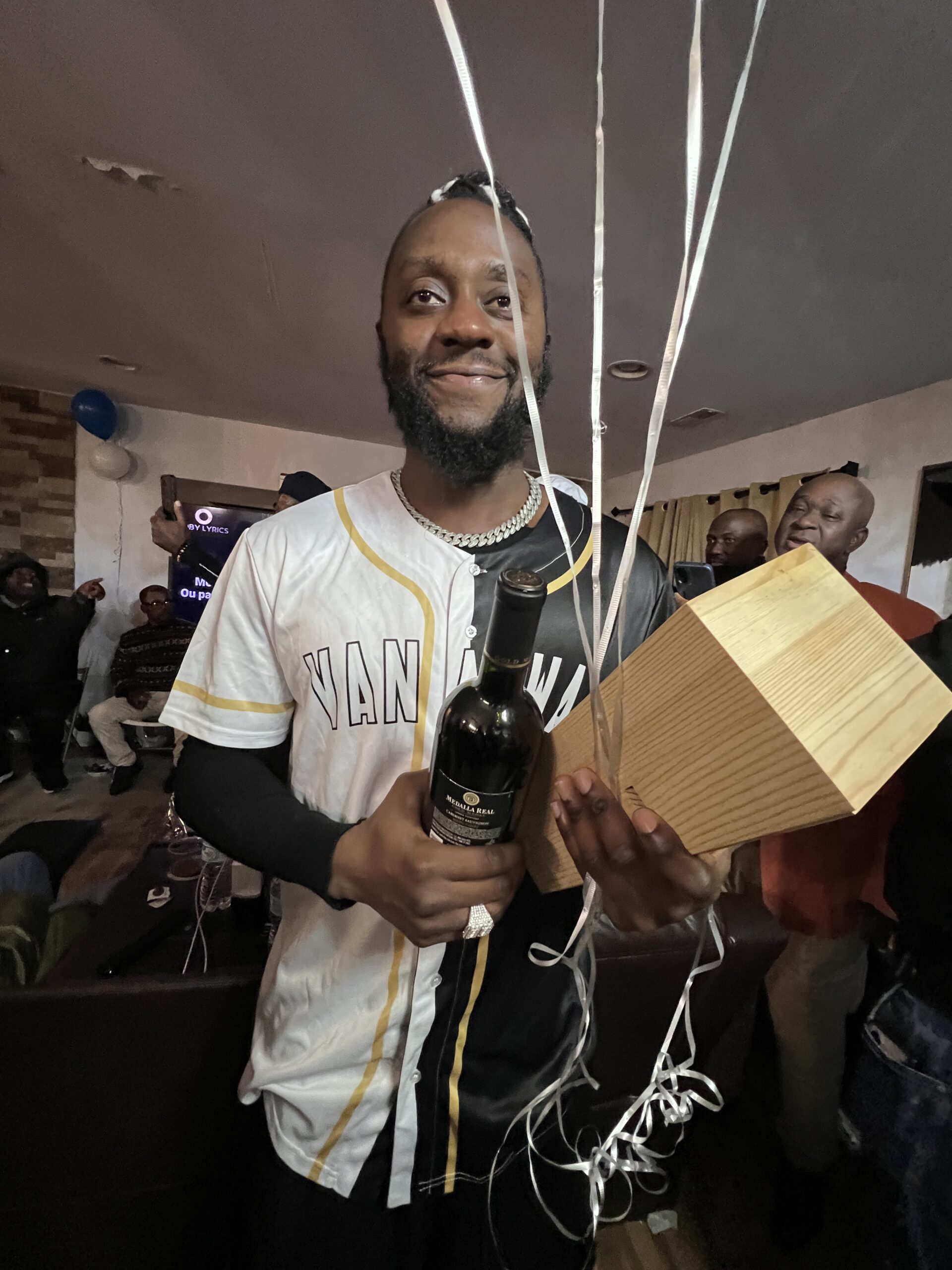

The scene was intimate and electric. Metallic streamers caught the light like confetti; a large screen cycled Afrobeats videos; laughter ricocheted off the walls. Guests spilled through the door—friends, former players, coaching colleagues, and family—bringing with them the warmth of home in the form of hugs, gifts, and trays of food that smelled like memory. At the centre, Ayinde wore a custom Black-and-white baseball jersey emblazoned “VAN AWWAL” and the number 29, relaxed and candid as he accepted a bottle of wine presented in a wooden box given to him by his friends.

The menu read like a love letter to Nigeria: glossy jollof rice, fragrant fried rice, steaming bowls of pepper soup, fried yams, and platters of roasted meats carried aloft like trophies.

At one point, a guest—Quam Olaogun-Dickson—hoisted a large piece of roasted meat in the air—the moment a photo-op became a communal cheer. Spirits flowed freely—tequila, whiskey, and vodka punctuated the evening—and a playful shot, poured directly into a friend’s mouth, captured the careless joy of the night.

Yet the party was more than food and music. It was a gathering to honour a life that moves between continents and systems, someone who scouts futures on muddy pitches and shapes careers in heated gyms.

Ayinde’s CV reads like a lived geography of football: playing stints in England with Thamesmead Town and Welling United, time at Blackpool Academy, coaching roles in southern New Jersey clubs, and a spell as men’s assistant coach at Camden County College. He is the head coach at Saint Joseph Academy in Hammonton. He holds an array of credentials—FA Level I & II, multiple USSF licenses, PFSA scouting certifications, and a football-psychology qualification—while pursuing his UEFA B licence in London.

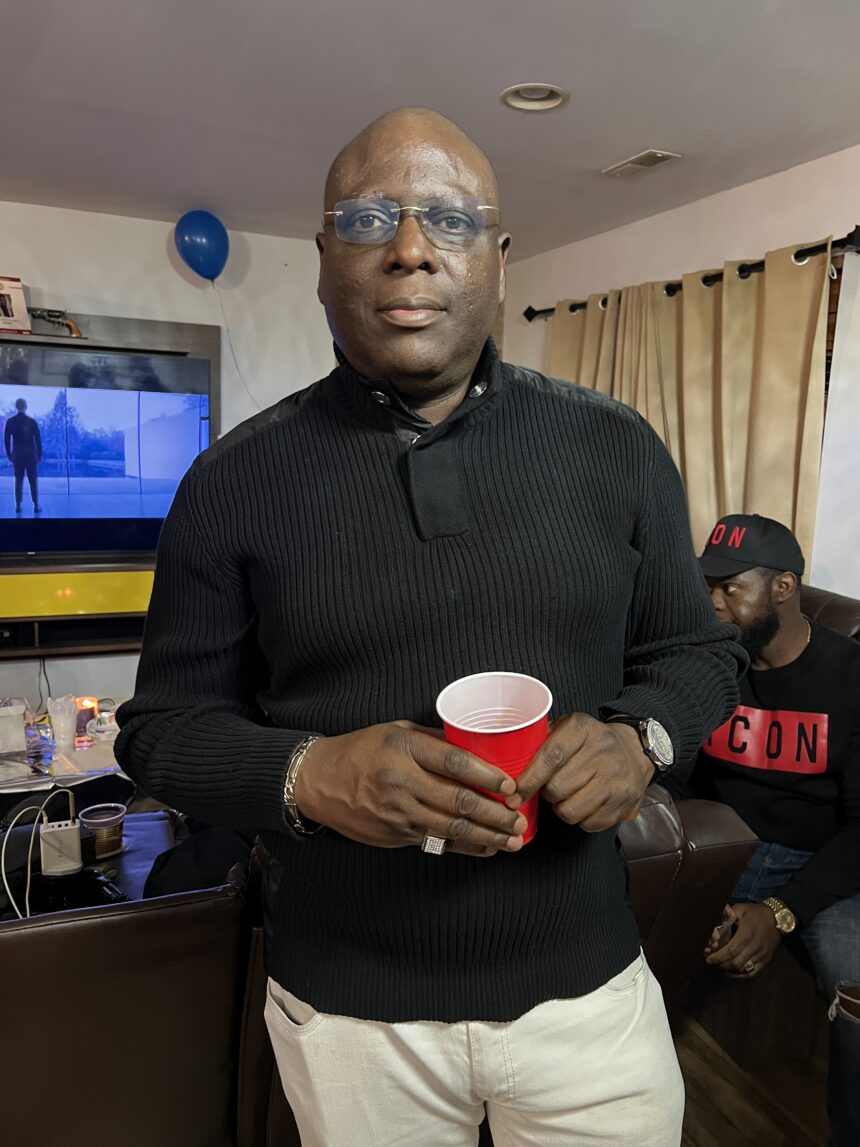

Those credentials explain the guest list: a who’s who of diaspora supporters and football insiders—Dimeji Bilewu, Labode, Deola Awogbemila, Quam Dickson-Olaogun, and Ade Ojo among them—people who have watched Ayinde’s quiet, persistent construction of a scouting and coaching legacy.

They arrived bearing gifts, banter, and praise. At one point, a spirited argument—football-tactic heat more than ill will—flickered across the room. It was brief, contained, and folded back into the evening by a round of jokes and the beat of an Afrobeats classic.

There were markers of achievement at the heart of every congratulatory toast. Under Ayinde’s tutelage, youth teams captured EDP championships, state cup honours, and local acclaim; he was recently named second-best coach in the Cape-Atlantic high school season. As a talent spotter for the NFF, he has bridged local clubs with national opportunities. This raw carries with it the quiet responsibility of shaping the Super Eagles of tomorrow.

When he took the mic—unrehearsed, sincere—Ayinde’s gratitude was the pivot of the night. He thanked those who had travelled, those who had mentored him, and the young players who keep him awake at night with possibility.

For many present, the party was not only a celebration but an affirmation, an acknowledgment of a man who has used his gifts to create space for others, who has turned scouting into a vocation and community into an operational principle.

By midnight, the living room had surrendered to the dancefloor. Women and men traded steps; voices rose in choruses; shoes were surrendered to the rhythm. It was, in microcosm, a map of what the Nigerian community abroad often looks like—rooted in home, expansive in reach, irrepressibly alive.

Awwal Adegoke Ayinde’s 37th was not a headline spectacle. It was better: an intimate chronicle of service, a night where achievements were toasted, stories rewoven, and a community—far from Lagos yet loyal to it—came together to say, in music, food, and laughter, that his work matters.